Increased intracranial pressure

SYMPTOMS

What is intracranial pressure? What is the normal range of intracranial pressure?

The adult cranial cavity is a relatively enclosed space, with its rigid bony walls maintaining a fixed volume (approximately 1400–1700 mL), unlike a balloon that can expand or contract. The contents of the cranial cavity mainly include brain tissue (about 80%), blood (about 10%), and cerebrospinal fluid (about 10%).

Cerebrospinal fluid is continuously produced primarily in the lateral ventricles of the brain, then flows through the ventricular system, dispersing evenly into the space between the meninges and brain tissue (also called the subarachnoid space). Eventually, it is absorbed into the bloodstream via capillaries in the brain and spinal cord, forming the important "third circulation"—the cerebrospinal fluid circulation—which plays a vital protective, supportive, and nutritive role for the brain and spinal cord.

Intracranial pressure refers to the pressure exerted by the contents of the cranial cavity on its inner walls. When cerebrospinal fluid circulation is unobstructed, it is typically represented by the hydrostatic pressure measured via lumbar puncture in the lateral decubitus position. Therefore, lumbar puncture, a minimally invasive method, is commonly used clinically to measure intracranial pressure. When necessary, invasive intracranial pressure monitoring systems can also be employed for continuous measurement. The normal intracranial pressure range is 80–180 mmH2O in adults and 40–100 mmH2O in children.

What is increased intracranial pressure? How does it develop?

Increased intracranial pressure refers to a condition where intracranial pressure consistently exceeds 200 mmH2O (in adults), also known as "intracranial hypertension syndrome," "intracranial hypertension," or "elevated intracranial pressure." It is a potentially severe complication of neurological damage.

Due to the fixed volume of the cranial cavity, any increase in the volume of its contents—such as brain tissue, blood, or cerebrospinal fluid—can lead to elevated intracranial pressure. The body can partially compensate by regulating cerebral blood flow and cerebrospinal fluid dynamics, but beyond a certain threshold, decompensation occurs, leading to serious consequences, including life-threatening conditions.

What are the common manifestations of increased intracranial pressure?

Increased intracranial pressure can cause a series of clinical symptoms, with the classic triad being headache, projectile vomiting, and papilledema. Depending on the cause and mechanism, symptoms may appear acutely or progress chronically, with the latter often being subtle and easily overlooked.

- Headache: The most common and often earliest symptom, typically localized to the frontal or temporal regions but may extend to the occipital or cervical areas. The pain is usually persistent, throbbing, or bursting, worsening intermittently, and is most severe upon waking in the morning or at night, often waking the patient in the early hours. Nighttime awakening due to pain is relatively specific to intracranial hypertension and warrants high suspicion. The severity varies based on the underlying cause and individual tolerance, but actions like coughing, sneezing, bending forward, or straining can exacerbate it.

- Projectile vomiting: Often occurs with severe headaches or on an empty stomach in the morning. Vomiting may happen suddenly, sometimes projectile, without preceding nausea, and can be triggered by head movements like turning or lowering the head.

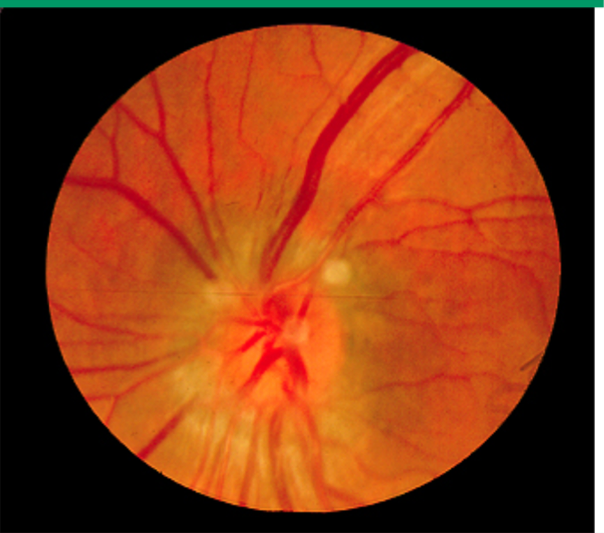

- Papilledema: A key and reliable objective sign of increased intracranial pressure, observed via fundoscopy as optic disc swelling, blurred margins, loss of physiological cupping, and engorged retinal veins. Severe cases may show hemorrhages (Figure 1). Acute cases may show minimal changes, while chronic cases exhibit typical findings. Early papilledema may not impair vision, but progression can lead to central scotomas, transient visual obscurations, and eventually persistent vision loss, optic atrophy, or blindness.

Figure 1 Typical fundoscopic image of papilledema (Source: Reference [1])

Additionally, depending on the cause, patients may experience other neurological symptoms or signs, such as limb weakness, numbness, facial numbness, facial paralysis, diplopia, blurred vision, or dizziness.

What life-threatening consequences can increased intracranial pressure cause?

The severity of outcomes varies based on the cause and progression of intracranial hypertension. In severe cases, it can lead to alterations in vital signs, such as consciousness (e.g., coma, lethargy), mental state (e.g., delirium, agitation, hallucinations), respiration (e.g., irregular breathing, bradypnea, or apnea), circulation (e.g., bradycardia or tachycardia, hypertension or hypotension), and temperature (e.g., sustained central fever, followed by hypothermia due to respiratory failure).

Rapid progression of intracranial pressure can cause dramatic changes in vital signs, potentially leading to death within minutes to hours. Severe intracranial hypertension may also trigger complications in other organs, such as upper gastrointestinal bleeding, neurogenic pulmonary edema, acute kidney injury, diabetes insipidus, cerebral salt retention, or cerebral salt-wasting syndrome.

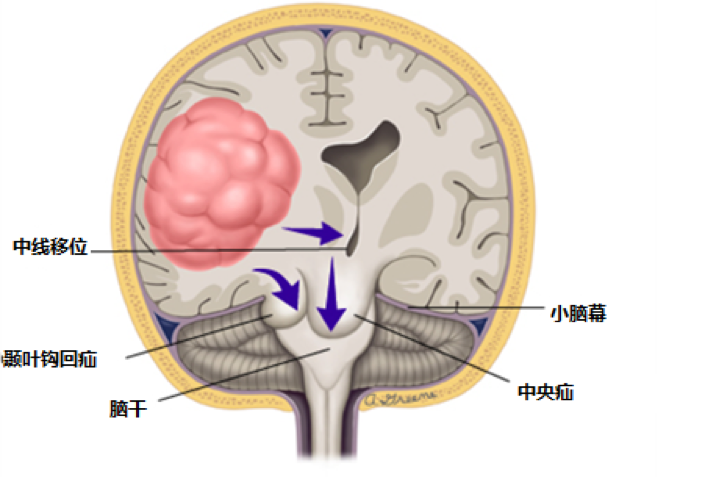

Beyond vital sign disturbances and systemic complications, increased intracranial pressure can lead to another life-threatening condition—brain herniation. Brain herniation occurs when severely elevated pressure forces brain tissue to shift into compartments with lower resistance, compressing neural and vascular structures (Figure 2 illustrates the mechanism of herniation due to a unilateral space-occupying lesion). This exacerbates intracranial pressure, creating a vicious cycle that can be fatal.

TREATMENT

How to Treat and Relieve Increased Intracranial Pressure?

Increased intracranial pressure (ICP) is a critical condition in neurology and neurosurgery. Once suspected, prompt medical attention is necessary to identify the cause and mechanism, allowing early intervention to prevent severe complications. The best treatment involves addressing the underlying cause. Additional measures include reducing intracranial pressure (e.g., using dehydrating agents, diuretics, or cerebrospinal fluid shunting when necessary) and preventing or managing complications.

Beyond medical treatment, certain lifestyle adjustments can help lower intracranial pressure, such as:

- Lifestyle:

- Patients should rest in bed with the head and upper body slightly elevated (15°–30°), maintain a quiet environment, and avoid excessive pillow height, neck twisting, or chest compression.

- Avoid emotional agitation, constipation, straining during bowel movements, and urinary retention. Laxatives may be used if needed.

- Refrain from vigorous coughing, bending over, or similar actions that may trigger a sudden rise in ICP.

- Hyperventilation can rapidly reduce cerebral blood flow and lower ICP by decreasing carbon dioxide levels. However, it may cause rebound effects and should only be used as an emergency measure for life-threatening conditions like brain herniation, under strict medical supervision.

- Diet: Patients should increase dietary fiber to prevent constipation, avoid high-sodium foods, and ensure adequate vitamin intake.

Regardless, increased ICP is a medical emergency requiring immediate evaluation to determine the cause and initiate treatment.

DIAGNOSIS

Under what circumstances should one seek medical attention for increased intracranial pressure?

Adults with increased intracranial pressure should seek immediate medical attention if they experience the following symptoms or conditions:

Acute severe headache or chronic progressively worsening headache, especially if it wakes the patient from sleep in the early morning, or worsens with actions such as coughing, sneezing, bending forward, or straining during bowel movements—regardless of whether it is accompanied by projectile vomiting, blurred vision, or other symptoms—requires prompt hospital evaluation.

For patients diagnosed with chronic idiopathic intracranial hypertension, whether receiving medication or surgical treatment, long-term regular follow-up is essential to monitor disease progression. If symptoms such as rapid vision loss, unsteady gait, worsening headache, nausea/vomiting, or mental status changes occur, immediate medical reevaluation is necessary to assess for a sudden rise in intracranial pressure.

POTENTIAL DISEASES

What are the possible causes of increased intracranial pressure?

In adults, increased intracranial pressure may be associated with many diseases, which can be classified by pathogenesis as follows:

- Diseases causing cerebral edema: Increased water content in brain tissue can lead to brain volume expansion, thereby raising intracranial pressure. This is the most common cause of elevated intracranial pressure and can occur in various conditions such as traumatic brain injury, inflammation, stroke, tumors, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, and poisoning.

- Intracranial space-occupying lesions: These refer to additional masses within the cranial cavity that occupy intracranial space, compressing adjacent tissues and obstructing cerebrospinal fluid circulation, further increasing intracranial pressure. Common conditions include intracranial tumors, hematomas, abscesses, and granulomas.

- Diseases causing increased intracranial blood volume: Expansion of intracranial vascular beds or impaired venous return can elevate intracranial blood volume, leading to increased intracranial pressure. Common causes include carbon dioxide retention due to various factors, post-traumatic cerebral vasodilation, intracranial venous system obstruction, or elevated superior vena cava pressure from various etiologies.

- Increased cerebrospinal fluid: Excessive cerebrospinal fluid production, impaired absorption, or circulation blockage can increase cerebrospinal fluid volume, raising intracranial pressure. Overproduction is often seen in choroid plexus papillomas or intracranial inflammation; impaired absorption may occur due to red blood cells obstructing arachnoid granulations after subarachnoid hemorrhage; circulation obstruction can result from developmental malformations, tumor compression, post-inflammatory or hemorrhagic adhesions, etc.

- Reduced cranial cavity volume: In rare cases, premature cranial suture closure can narrow the cranial cavity, causing increased intracranial pressure.

Diseases related to the above mechanisms may present acutely or progress chronically. Tumors and developmental disorders often progress slowly, while trauma, inflammation, stroke, and poisoning typically manifest acutely. However, chronic conditions may worsen suddenly, and acute diseases can evolve into chronic states.